By Paolo Coluzzi

Continuing Paolo Coluzzi’s backpacking journey through several countries in Asia. This time, he visited China, the ancient ‘Land of the Red Dragon’.

China

China boasts the most ancient recorded history, and a rich and interesting culture. Officially, most Chinese do not follow any religion now; but the number of those returning to the traditional religions is slowly growing, particularly Buddhism and Taoism, the autochthonous philosophy/religion that shares many traits with Buddhism. Add to these, folk religions (often mixed with Taoism), the cult of ancestors and, last but not least, Confucianism. Even though thousands of religious structures were destroyed during the harshest days of Communism, many survived and are still extant, and the government, having changed its attitude, is now striving to restore and build anew. As yet another instance of Man’s limitations (if not stupidity) in his long history, Marx’s statement on religion being the opium of the masses was taken to the letter by most Communist regimes – including China, infamously – in spite of the fact that Marx most likely had no knowledge of Buddhist philosophy.

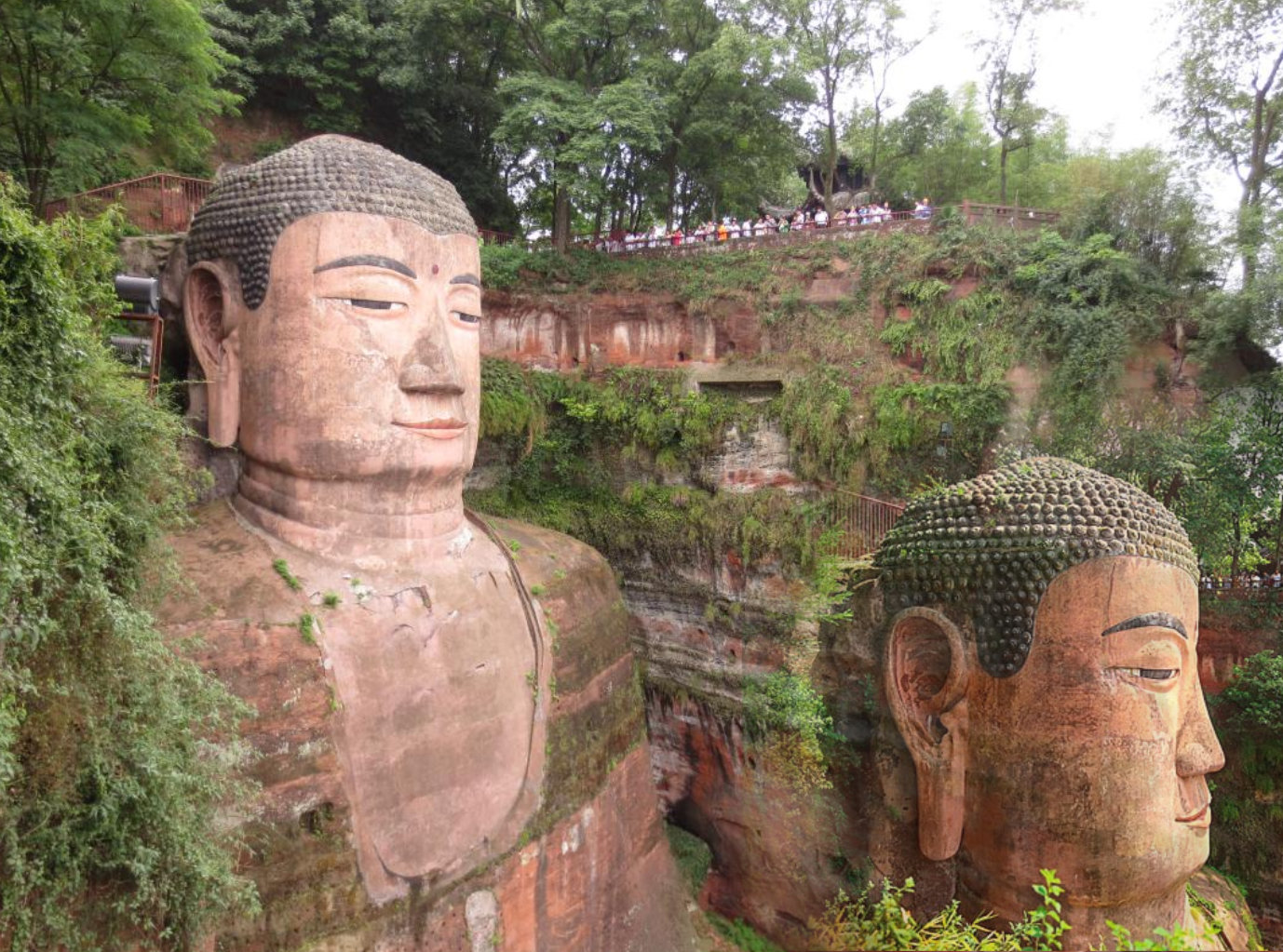

I first travelled to China in 2010, when I visited several Buddhist temples. But only five years later, during a trip to Chongqing and Chengdu, did I manage to visit one of its most remarkable and important Buddhist sites, the Dafo, the Giant Buddha of Leshan near Chengdu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the cultural treasures of China, together with several others such as the Buddhist paintings and sculptures located in various caves and on cliffs in different parts of the country (one of these sites, Dazu, is described briefly at the end of the following account).

The Dafo, the Giant Buddha of Leshan

The Giant Buddha of Leshan (June 2015)

Finally, the last day of the semester. The following afternoon, I’m off to Chongqing, in the People’s Republic of China. This time, I’m not travelling alone. Rie, my Japanese former girlfriend (‘former’ for the best of reasons, as we were married less than two months ago), is coming with me. I enjoy travelling on my own, but I’m happy to be sharing this Chinese experience with my wife, whose knowledge of Chinese will be an asset in a country where not many speak English. I had already obtained my visa whereas Rie, thanks to her Japanese passport, did not need one for a visit lasting less than two weeks.

The name ‘Chongqing’ might not ring a bell for many, but it’s a city with a long history. It is the most important river port and financial and commercial centre of Southwest China, a megalopolis of 15 million people, born at the confluence of the Jialing River with the great Yangtze, which has its source in the Himalayas and flows into the sea in Shanghai, 1,274 kilometres from Chongqing. We have two main reasons for this trip: to see our friend and former colleague Milena, who moved from the University of Malaya to Chongqing last September to start teaching at one of the local universities; and to visit the Giant Buddha of Leshan.

Due to a delay with our connection at Guangzhou airport, we arrive at Milena’s very late that night, but she is up waiting for us. The following day, we visit Ciqi Kou, a neighbourhood in Chongqing (once a village outside the city) that has retained its ancient Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) look.

The next morning, after registering at the local police station (mandatory for foreigners staying in a private household), we head for Central Station, an enormous new building not yet complete, to catch the one o’clock fast train to Chengdu. The sheer mass of people around us is impressive. And whereas in Europe a train may have at the most, say, seven or eight carriages, the one we get onto must have at least twenty. This accounts for the size of the station. Besides, everything here must work perfectly: two trains cannot arrive at the same time on two adjacent tracks, lest the throng be unmanageable. Every which way one looks, one sees staff directing the crowds in the right direction. Hats off to their perfect organisational skills.

The train is comfortable, with a bar and restaurant service, and fast (every now and again we touch 250 kilometres per hour). It runs for long stretches over high viaducts, allowing us ‒ except when going through a tunnel – a view over the urban area surrounding Chongqing and Chengdu and, between the two cities, over the Sichuan landscape of green hills, woods, ponds and tilled land broken here and there by the houses of small villages or farms. During the first stretch from Chongqing, we also notice some haze in the air, apparently quite common in this city, partly due to its geographical position and the climate and partly, I believe, to pollution. Fortunately, we find a clearer atmosphere in Chengdu. We arrive at Chengdu North Station in perfect time, having travelled 270 kilometres in exactly two hours.

From the station, also vast, we decide to try and walk to the guesthouse that Milena has booked for us, which looks fairly close on the map. The problem is, we are not yet used to the sizes of these cities or the scale of their maps. It takes us more than an hour to get to our guesthouse, in spite of the fact that Chengdu is much ‘smaller’ than Chongqing – i.e. only 9 million people. Here, too, the roads are wide, forming a regular weave with the long main streets stretching from north to south, or circularly forming ring roads, with several flyovers to speed up the traffic. And here, too, we notice the lanes for bicycles and motorbikes, which are electric-powered, and the ample pavements that, unlike in Malaysia, are busy, but never so much as to make walking difficult. Many of the buildings are relatively old, perhaps built after the Second World War, but there are also several modern skyscrapers, and lots of shops along the pavements.

We finally arrive at the guesthouse, which we find unfussy but pretty, as Milena had told us it would be. We take to it, and to the friendly and helpful young staff. Among the services they offer is the booking of trains and suburban buses, so we decide to book a bus to Leshan for the following morning. That done, we repair to our room for a freshen-up and rest, on the second floor (third floor by Chinese reckoning, where the ground floor is considered the first floor, like in the States), overlooking a wide courtyard, one of the walls decorated with drawings of pandas. Pandas are in fact native to this region. Just outside the city is the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, now one of the main attractions for tourists coming to Chengdu. Even if we wanted to, unfortunately, we would not have the time to visit it, having decided to privilege history and spirituality before nature. But leaving something unexplored bodes well for a second visit.

At five that afternoon, we start our tour of the city with the Wenshu Yuan, a Chan (Zen) temple and monastery built originally in the 7th century, and rebuilt around 1700. It is a vast wood-and-stone temple complex, built in a classic Chinese style, with sweeping roofs, buildings lined up one behind the other – between them, ample courtyards – and Buddhist monks milling around. Most evocative. Home to a bone relic of the famous Buddhist scholar, pilgrim Xuanzang, the monastery is also associated with a legend concerning its one-time resident Chan Master Cidu and the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Manjushri. Within the grounds are several points of interest, including a pointed, eleven-tiered pagoda, a vast library, and a crowded traditional tea house. Opposite the temple is a neighbourhood as can only be found in China: built in a traditional style, though new, with many charming, old-world shops selling new-world knick-knacks. As mentioned earlier, there is regret on the part of the government, made more evident by such projects, about the indiscriminate destruction of the nation’s historical heritage both during the Cultural Revolution and in the rush to modernity. After the temple, we move on to Tianfu, the city’s central square, where a big statue of Mao rises before the Sichuan Science and Technology Museum, before heading back to the hotel.

The following morning we rise at seven, for our 8.30-am coach to Leshan. The changeable weather of the preceding days has been replaced by a clear sky and warmer temperatures. It takes some time to leave the city, after which it is motorway all the way to Leshan, which we reach before 11 o’clock. At the coach station, a minibus awaits to take visitors to the entrance of the Archaeological Park where the Dafo, Leshan’s Giant Buddha, is located. Carved out of rock on the bank of the Minjiang River, from its great height of 71 metres it looks down on the confluence of three rivers. Getting off the minibus, we have a plate of the tasty local mian (noodles) at a small roadside restaurant, before heading towards the main entrance.

Buying our tickets, we make our way up the steps leading to the top of the big rock where the Ling Yun Buddhist Temple and the multi-eaved Ling Bao Pagoda are located. And there before the temple, a few dozen metres from us, the wonder: from the edge of the small plateau where we are standing, we see the boundless head of the Buddha looming up, with its seven-metre-long ear, and eyes each measuring over three metres in length. One becomes almost still in the presence of it. We edge to the railing placed along the clearing where the escarpment begins, in the middle of which sits this prodigious statue of the Enlightened One. From here, we finally see the Giant Buddha of Leshan in his entirety, 71 metres from the bottom where the river flows. What an incredible feat and immense act of devotion that was, 13 centuries ago, to undertake this. Carved in the 8th century CE, it is the biggest Buddhist sculpture in the world, now on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It forms part of the Mount Emei Scenic Area, where the first Buddhist temple in China was built in the 1st century CE. To one side are steep steps known as the Nine Bends Plank Road, which take us down as far as the colossal feet of the Buddha. The sight of the Dafo at different levels and heights, a dozen metres from oneself, fills one with awe, even when one reaches the bottom – near the river – and observes it from below. On the opposite side is another set of steps, longer and more gradual, which takes us back to the top near the head. We linger for a while, to take in the Buddha and the atmosphere, before heading for the exit, filled with what we have just seen.

At this point we have to look for a bus or a taxi to take us back to the coach station, but no sooner do we exit than a young man approaches us, offering us the inbound trip to Chengdu on a private coach that is due to leave half an hour later directly from here. Excellent. So, by about 6:30 pm, we are already back in Chengdu, in the coach station from where we departed that morning.

The following day, we have time enough to visit Qing Yang Gong, a most remarkable Taoist temple, before heading back to the train station for a fast train back to Chongqing, pleased to have seen another part of China – Chengdu and Leshan’s magnificent Buddha.

On the last two days of our stay in China, we visit Luohan Si – the Temple of the Bodhisattvas in Chongqing – and the Buddhist rock sculptures of Dazu, also on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Dazu is about 200 kilometres from Chongqing, but easy to reach by bus. There are about 50,000 rock sculptures in the area, spread over several sites. Of the two most famous sites, Bei Shan and Baoding Shan, we decide to visit the latter, located 16 kilometres from Dazu town. The Baoding Shan sculptures, for the most part representing Buddhist themes, were carved onto the rock on the side of a hill between the 12th and 13th centuries CE, under the supervision of the monk Zhao Zhifeng. There are statues of the Buddha (one of a reclining Buddha is 20 metres long), Bodhisattvas (luohan in Chinese), demons, a big Buddhist Wheel of Life, various animals, and other sundry characters.

On the Saturday, a week after our arrival, it is time for us to leave. It would have been good to have had a few more days to enjoy this interesting country, but our university calls. Luckily, the following day is a Sunday and so we can rest a little, mentally revitalised by our time in the Middle Kingdom.

About the Writer :

Paolo Coluzzi is an Associate Professor at University of Malaya, KL where he teaches Italian and sociolinguistics. He first became interested in Buddhism at the age of 17. It is a fascination which has deepened over the years, thanks to contact with the many monks, Dharma experts and fellow-travellers he has encountered on his journeys.